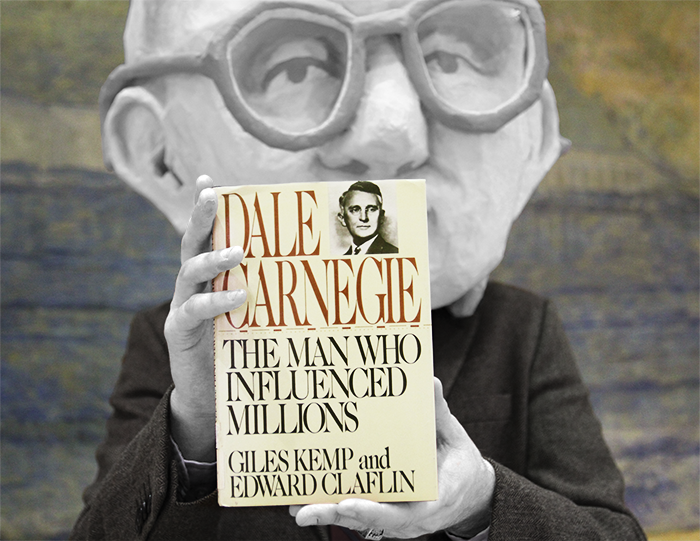

Below is a conversation and series of photographs I worked on in collaboration with Catherine McMahon for N52: On Art + Research at MIT. We discuss Dale Carnegie, his book, and my animation (both titled How to Win Friends and Influence People). Together Catherine and I made a series of photographs that take their titles from the chapters of a Carnegie biography titled Dale Carnegie: The Man Who Influenced Millions.

Figure 1. Dale Carnegie: The Man Who Influenced Millions. 2010.

“I realize now that healthy people don’t write books about health. And, in the same way, people who have a natural gift for diplomacy don’t write books on How to Win Friends and Influence People. The reason I wrote the book was because I have blundered so often myself… .” — Dale Carnegie [1]

Who is Dale Carnegie, anyway?

Jess Wheelock: Sometimes when I tell people about how I am making an animation with the book How to Win Friends and Influence People where I hang around with Dale Carnegie, they don’t always get it.[2] Especially if they don’t know my work — I think they get confused. First of all, a bunch of people don’t know who Dale Carnegie is and they think I’m collaborating with him or something…(laughs)

Catherine McMahon: No, no that’s the thing — that’s what’s funny. I was vaguely familiar with him, but Dale Carnegie is sort of an obscure figure.

JW: That’s what I like about making Dale a character — because he is such a non-character outside of the text. What does the guy who wins friends and influences people…what does he do on the weekend?

CM: So in the first photograph we made, Dale is holding a copy of his biography (Figure 1).

JW: Right.

CM: By the way, did we ever figure out who Giles Kemp and Edward Claflin are?

CM: I wonder who they are or what they do.[3] Really, who writes a biography about Dale Carnegie anyway?

Who makes an animation about Dale Carnegie anyway?

CM: I am thinking about some of the work I have seen in ACT (MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology) that responds in some way to the institutional make-up of this place and the difficulties that sometimes come along with that. It’s not that the work aims to be about these things per se, yet one cannot help but react to the immediate situation.

JW: Sure, one is situated in the institute and that creeps into the work.

CM: So I almost wonder if in a way, this whole Dale thing with you is a reflection of this — in the way that the sciences or say, Sloan (School of Management) hover as shadows of presumed legitimacy over something like the art program here at MIT. How do you engage in a topic that responds to the authority of the institute or the pressures of the institute in relationship to the art program? Making a work about a business guru seems to be one way to deal with this.

JW: I think in some ways it was a response to the Media Lab and their demos — how they have to sell themselves in 30 seconds.[4]

CM: The elevator pitch.

JW: Right. The students all over Cambridge are so poised in that way. Yet when I had to talk about what I did, it seemed messier somehow…it didn’t quite fit. So doing a piece about a self-help book seemed like an opportunity to me. It gave me a clear antagonist to struggle against.

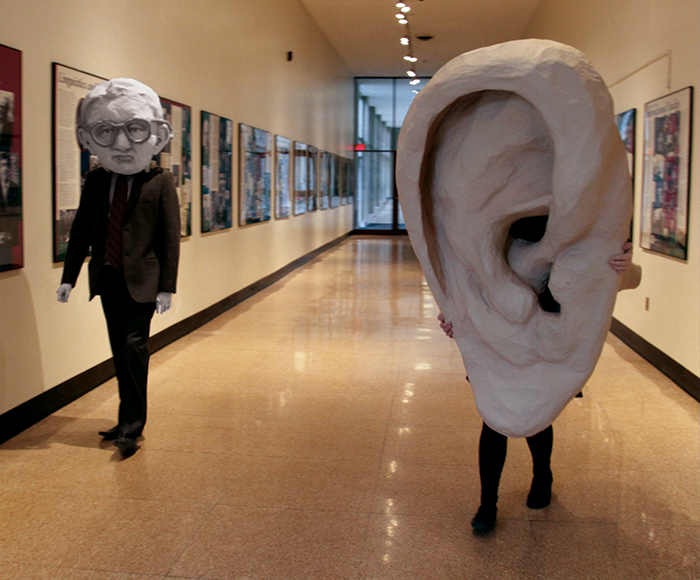

Figure 2 & 3. Floods, Frugality, and Faith. 2010.

CM: That’s so funny, so you were both teaching yourself a skill and at the same time disassembling it entirely.

JW: Yeah, I thought of the project as just acting out the book. There is this quality to social relations where it is an issue of performance. Dale, or maybe the book as a whole, is like a sort of Cyrano — a voice that helps you act as a better version of you. It gets back to issues of voice and authorship.

CM: The first chapter, “How to Read This Book” invites you to mark up the pages and write anecdotes or observations in the margin — almost co-authoring the text. Animating it is one way to mirror this suggestion of literally writing yourself into the text.

JW: Right, and by using Dale’s title as the title for my animation, there is an extra confusion of authorship — or maybe a claiming of it.

CM: It’s interesting, too that you are a silent character in all these works and yet you are the one really pulling the strings of what’s going on. At least in the animation you are always silently listening to Dale and yet you are in fact the author what transpires.

JW: (laughs) Yeah, he’s a bit of a ventriloquist dummy in that way…

CM: It’s what you’ve said about performance in the past — you find performance incredibly uncomfortable and yet you make use of that tension by embracing it. You play with awkwardness and you play off the fact that you don’t want to speak in front of all these people. So the work becomes about you finding ways around this problem.

JW: Yeah, like Ah Güzel İstanbul (Oh Beautiful Istanbul).[5] I was terrified to perform. I always get that shaky, nervous sound to my voice. So I had to figure out a way around it. I built the performance around someone else narrating my actions for me and I discovered that I was able to throw my voice, in a way, using narration.

Figure 4. A Farmboy in Show Business. 2010.

Figure 5. Business and Friendships. 2010.

CM: The narration makes you, the performer into an object, too.

JW: Right. That’s how I began thinking of myself as material for the work — as this object with all sorts of limitations that I have to deal with. Working around them became a way for me to generate work. Like if I am nervous about something, I have to own it. That’s going to become part of the work…part of my voice.

Are you listening to me?

CM: In these photos, we experimented a lot with exaggeration of human form. I wonder how you think about that, in terms of the play with scale that happens.

JW: I like all of the props being a bit off in scale, a bit wrong. Like when you use the smile prop, it is just a little bigger than the size of a regular smile — it’s almost grotesque.

CM: But the ear is really off…

JW: Yes, it’s literally the same size as me.

CM: One thing I really like about the ear was that there was a kind of labor involved in carry it around all day long as we shot the photos. I like the imagination of you following around your ambulatory professor or mentor while carrying this giant object — laboring after him or trailing along with your giant ear to make sure you really learn his lessons.

JW: When I was first using the imagery of the big ear in the animation, it was like a shield. Well, it was like a shield and a catcher’s mitt. Holding it, I was trying to catch the words that were coming at me. But then in actually building it and in these photos…it does become a weight and it becomes more about the labor of holding it up. But I think it is still an object you can hide behind.

CM: You can hide behind it in these photos — but it looks so uncomfortable to deal with. Sometimes you don’t look like you’re hiding behind it, but struggling to hold it up. I don’t want to be too literal or simplistic, but it seems to evoke the struggle one has in dealing with the expectations that come along with maintaining a charming personality.

JW: Yeah, but I think it is also something else. Listening it a good example — it’s this thing that you know you should do…it’s not necessarily a hard task…but it’s so easy to wander off in your mind when someone is talking. Something about making that very physical, it shows the way the body fails, or that you can only listen for so long, or…hmmm…I don’t know how to say this exactly…

CM: Well, maybe it’s that no matter how ideal our intentions are there are very physical limits to our attention span, on our ability to listen, on who intimidates us, or who doesn’t. I mean you might go into a room all ready to win people over and then someone wearing the wrong color tie might throw you off.

JW: (laughs) I think that’s happened to me…

CM: You have the best intentions and then you realize that whatever it is you carry around with you can fail in the face of those intentions. It is great to physicalize this problem in the form of objects. The ear both shield and at the same time makes us aware of the awkwardness by emphasizing the fact that you are really listening to someone. You can hide behind these objects and yet you are also drawing attention to what it is that you are doing.

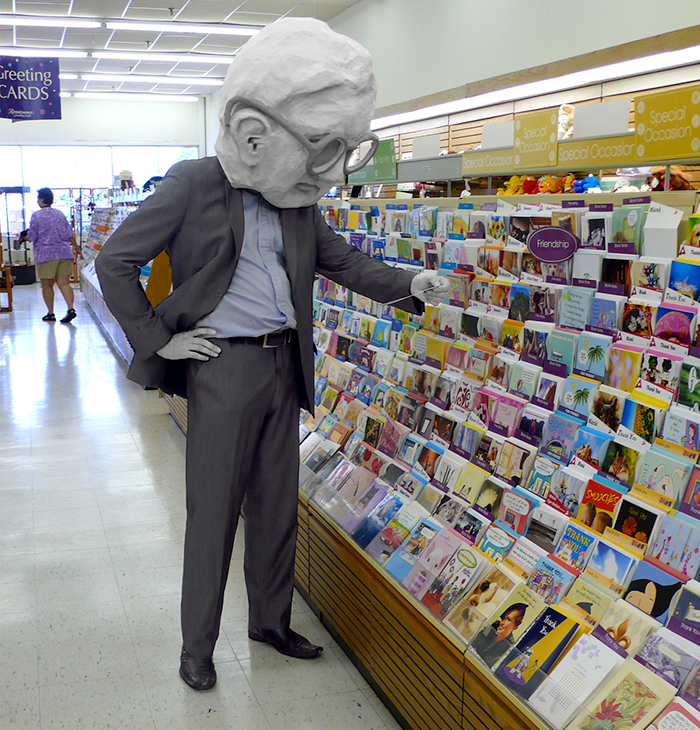

Figure 6. Learning by Doing. 2010.

Jess, didn’t you learn anything from Dale?

JW: After looking at the photographs we took together, for me they seemed to work better when Dale was performing tasks: wading through a river, fixing his glasses, buying a greeting card. I especially like the picture of him looking at greeting cards — because greeting cards are already such a weird thing and you can then wonder who he is buying it for and why.

CM: I agree about the greeting cards: they are bizarre. They are all about helping you to speak when you lack the words yourself and yet…for all the time spent (and people spend forever) picking out the cards to get that perfect message or joke, I’m not sure it really translates to the reader. Does anyone who gets these cards take the pre-written messages to heart? Maybe I am just cynical, but no matter how perfectly phrased the message, I always see the words as an ambiguous sign of good intentions vaguely floating on the page. Along with a sense that the card represents some sort of duty carried out…as if the birthday could not be sanctioned without the requisite card. I have a similar feeling about Dale. Is he helping people to speak with their own voice? Or is his voice routed through them as a series of well-meaning and better-stated social niceties?

JW: I do think that is the main tension that people have with the book: it’s this issue of sincerity. There is this conception that somehow learning all these rules makes you less honest or sincere. Or just less…

CM: You.

JW: Right.

CM: That’s something to ask about Dale. It’s great to win friends and influence people. It’s great to learn those skills. I think more and more we really realize that we need those skill to get our points out there. But at what point does it eclipse your own personality? At what point is one’s awkwardness wonderful…or even a strength?

Figure 7. From Public Speaking to Human Relations. 2010.

Figure 8. Be Yourself. 2010.

Footnotes

[1] Claflin, Edward and Giles Kemp. Dale Carnegie: The Man Who Influenced Millions. (New York, NY: St Martin’s Press, 1989) p.144 ↑

[2] In my animation, I fall into Dale Carnegie’s 1937 self-help book How to Win Friends and Influence People and am mentored by the author, who gives me advice and some strange tools to help me deal with people. ↑

[3] Claflin and Kemp, 1989. Both Edward Claflin and Giles Kemp were graduates of Dale Carnegie’s courses. According to the book jacket, “Giles Kemp is the executive vice president of a direct-marketing packaging firm. He lives in Scarsdale, New York. Edward Claflin produced Jack Carew’s You’ll Never Get No for an Answer and coauthored, with Dennis Corner, The Art of Winning. ↑

[4] Private companies provide nearly 100% of the funding to MIT’s Media Lab. Twice a year, researchers present demonstrations of their work to these sponsors. ↑

[5] Ah Güzel İstanbul (Oh Beautiful Istanbul) is a performance that retells my understanding and misunderstanding of the 1966 Turkish film Ah Güzel İstanbul. I watched the film Ah Güzel İstanbul, but the movie does not have subtitles and I do not speak Turkish. Using toy theater, shadow theater (Karagöz), and video, I retell my understanding of the story, weaving myself and my struggles into the piece. The performance is narrated in Turkish by Aylin Yilidirim and subtitled in English. ↑